My five favorite roll-and-write games

Plus nine honorable mentions, because there are too many great games to limit myself

In preparing to write this newsletter, I walked over to my shelf stocked with roll-and-write games and stared. I knew I wanted to write about my favorite roll-and-write games, but how was I going to narrow the list down to just five? Should I write about my top 10? 20? But in the end, it actually wasn’t that hard. I found the five I wanted to feature here without any real trouble, and I wrote about a (large) handful more roll-and-write games in an honorable mentions section.

Before we dive into this, let’s talk definitions. What’s a roll-and-write game, and does it include games where you don’t roll dice? A roll-and-write game, in the strictest sense, is a game in which you roll some dice, then you write something on a sheet of paper. I mean, that’s the basic idea, at least. There’s a ton of nuance that needs to go between those two events, and that’s really where the game sits, unless you particularly like writing on paper. (I’d advise you to get into fountain pens if that’s the case. You may not regret it, depending on how impulsive your purchases are. Anyway!)

What about games in which you’re flipping a card, you might ask? I think that counts here. I’m not going to call it a ‘flip-and-fill’ (which I’ve occasionally done — not trying to make this a negative thing), and I will, in fact, be placing them in the same category as a game with dice. The first key element is some sort of randomized input, whether it’s by cards, by rolling dice, or by radioactive decay, and the second key element is that you make a decision based on that randomness and denote that specific decision by writing on some sort of media, whether it’s paper or a laminated board on which you use dry-erase markers.

Some games will not fit into the list. I’m OK with that, and I need you to be, too. For example, Wordsy (Hova, 2017), a fantastic word-spelling game that I wrote about last week, is not a roll-and-write game, even though there are randomly selected cards from a deck, and you write your answer on paper. I’m also going to exclude games like First-Class Letters (Hayward, 2025), even though it bills itself as a roll-and-write game. (It doesn’t come close to the top five, so maybe that’s neither here nor there.) With a word-spelling game (or even most word games more generally), if you’re not using letter tiles or cards, you’re typically writing your answers down. There’s just not an alternative. Even Peggy Hill’s beloved Boggle (Cooke and Turoff, 1972) isn’t going to make the list. Is this just bias against word-spelling games? Maybe! I don’t think so, though. I love those games, but there’s a certain ineffable sense of ‘roll-and-writeness’ in which those games don’t participate. I don’t make the rules. (Wait, for this newsletter? Maybe I do. We’ll just say the person writing the parenthetical does. I’ll call that my ‘editor’ persona.)

At any rate, let’s talk through some of my favorite roll-and-write games. We’ll start with honorable mentions.

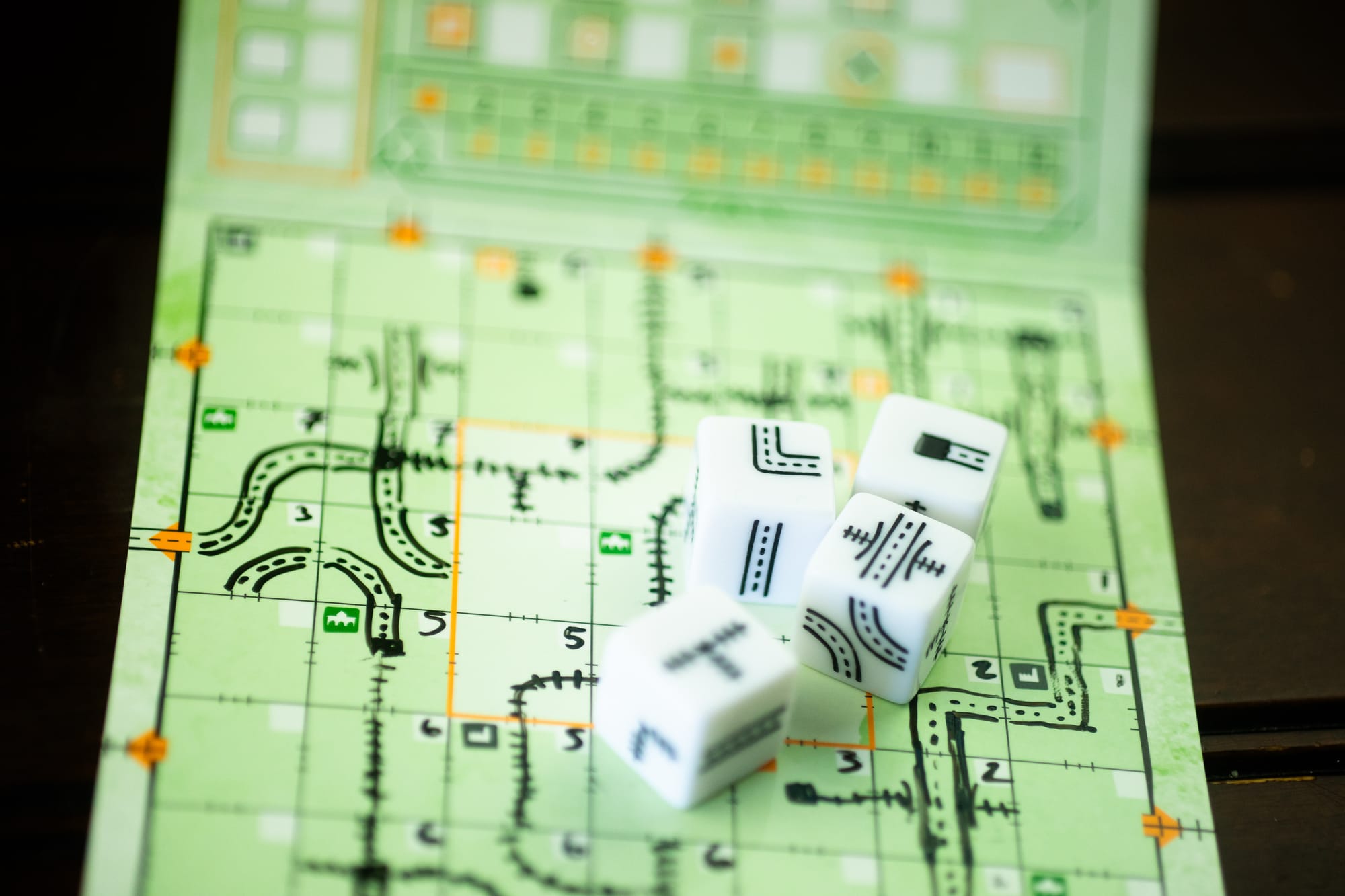

French Quarter, Floor Plan, Encore!, On Tour and Welcome To | Photos by Matt Montgomery

- Encore! (Inka and Markus Brand, 2016) is one of the rare roll-and-writes released before 2017, and it stands up well today. You’re marking off spaces in a color-blocked grid, and you earn points for marking all the boxes in a column or of a color. It’s a simple premise, and I love it for that. Designed by Inka and Markus Brand, illustrated by Leon Schiffer, and published by Schmidt Spiele.

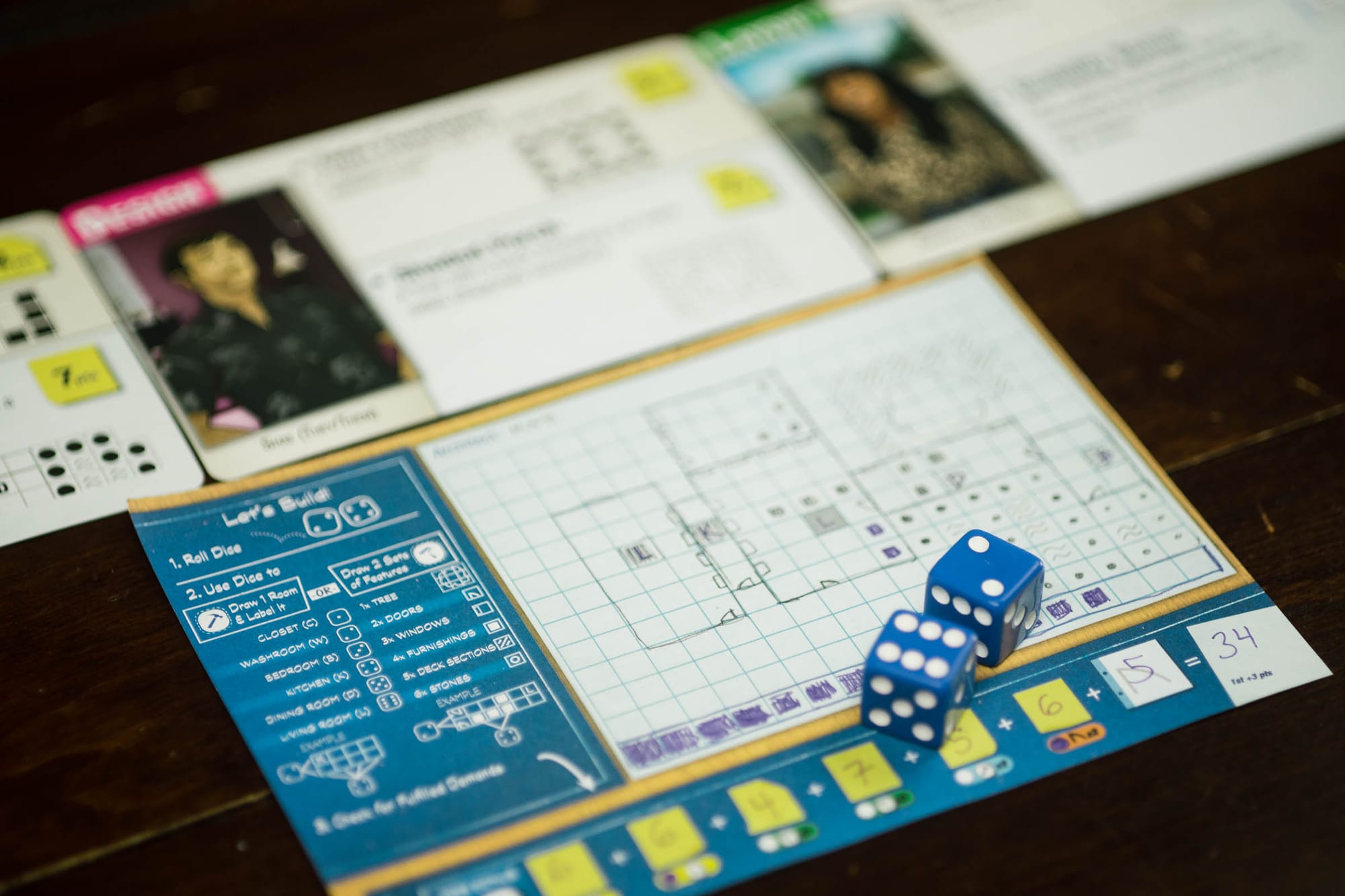

- Floor Plan (Tupy, 2020) has players building a house floor plan to suit different criteria on scoring cards, and it’s a bit of fun. Not the deepest game, and it maybe takes longer than it should, but I’ve quite liked it. Designed by Marek Tupy and illustrated by Dan Dougherty. This one’s unfortunately out of print, and its initial publisher seems to have had some dodgy Kickstarter dealings. This is widely available in the BGG marketplace if it’s up your alley.

- French Quarter (Hill, Pinchback and Riddle, 2024) is a great roll-and-write themed around New Orleans. You’ll be moving around a map of the city, collecting bonuses, and aiming to have things cascade upon each other for a lot of points. This is a great one, and the design team is unrivaled. Designed by Adam Hill, Ben Pinchback and Matt Riddle; illustrated by Marlies Barands and Snow Conrad; and published by Motor City Gameworks and 25th Century Games.

- On Tour (DeShon, 2019) is a network-building game about taking a band on tour across the United States or Europe, or in the sequel, Paris or New York. It’s a bit tricky, and you’ll be rewarded for good planning (and, realistically, good mitigation). I love the theme and the big ol’ boards. Designed by Chad DeShon, illustrated by Anca Gavril, and published by Allplay.

- Qwixx (Benndorf, 2012) is probably my mother-in-law’s favorite game. She’s always itching to play. She’ll play it with five more people than the game recommends, because A) she loves the game, and B) she’s always wanting to include everyone in the fun. This is a quick-playing themeless roll-and-write, and it really is a pretty good one. Designed by Steffen Benndorf; illustrated by Oliver Freudenreich, Sandra Freudenreich and Tom McKendrick; and published in the U.S. by Gamewright.

- Roll to the Top (Joustra and van Moorsel, 2018) is another optimization puzzle with dice where you’ll want to place small numbers on the bottom of a structure (the Pyramids of Giza, the Eiffel Tower, the Major Oak, that sort of thing). It’s reasonably quick and reasonably challenging. I like it. Designed by Peter Joustra and Corné van Moorsel, illustrated by Horia Tundrea, and published by Allplay as Roll to the Top: Journeys.

- Rolling Realms (Stegmaier, 2021) and Rolling Realms Redux (Stegmaier and Titeca, 2024) is a roll-and-write game — or, perhaps more accurately, it’s a system that sort of emulates a few dozen other games in a roll-and-write fashion. I’ve really enjoyed my plays of this one, but I think it’s just a bit too wonky to make my top five. Designed by Jamey Stegmaier and Karel Titeca, illustrated by Miles Bensky and Marius Petrecsu, and published by Stonemaier Games.

- Three Sisters (Pinchback and Riddle, 2022) is a little bit heavier of a roll-and-write, with a rondel — meaning each round, you’re limited to a slice of actions you can select. It’s themed around farming, and it has the ever-so-delightful chaining-action-bonus thing going on. A real good game, this. Designed by Ben Pinchback and Matt Riddle, illustrated by Marlies Barends and Beth Sobel, and published by Motor City Gameworks and 25th Century Games.

- Welcome To… (Turpin, 2018) is one of the games in the big wave of games in the genre back in 2018, and it holds up well. It’s basically an optimization puzzle with, yes, bonuses that you get based on what spaces you fill. Designed by Benoit Turpin, illustrated by Anne Heidsieck, and published by Blue Cocker Games.

Well, here we are. I’ve given you a slew of honorable mentions. These games are, apparently, my top five roll-and-write games. One of them does use cards. I trust you’ll understand.

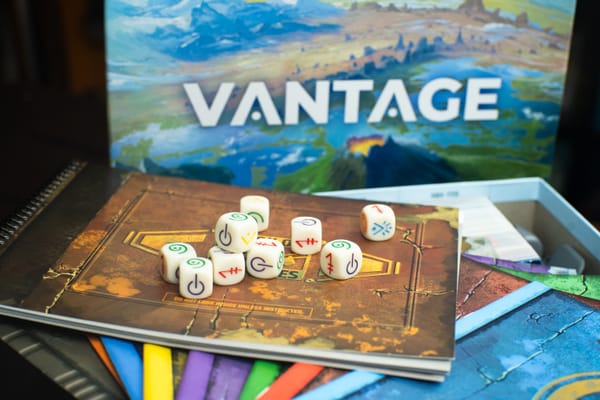

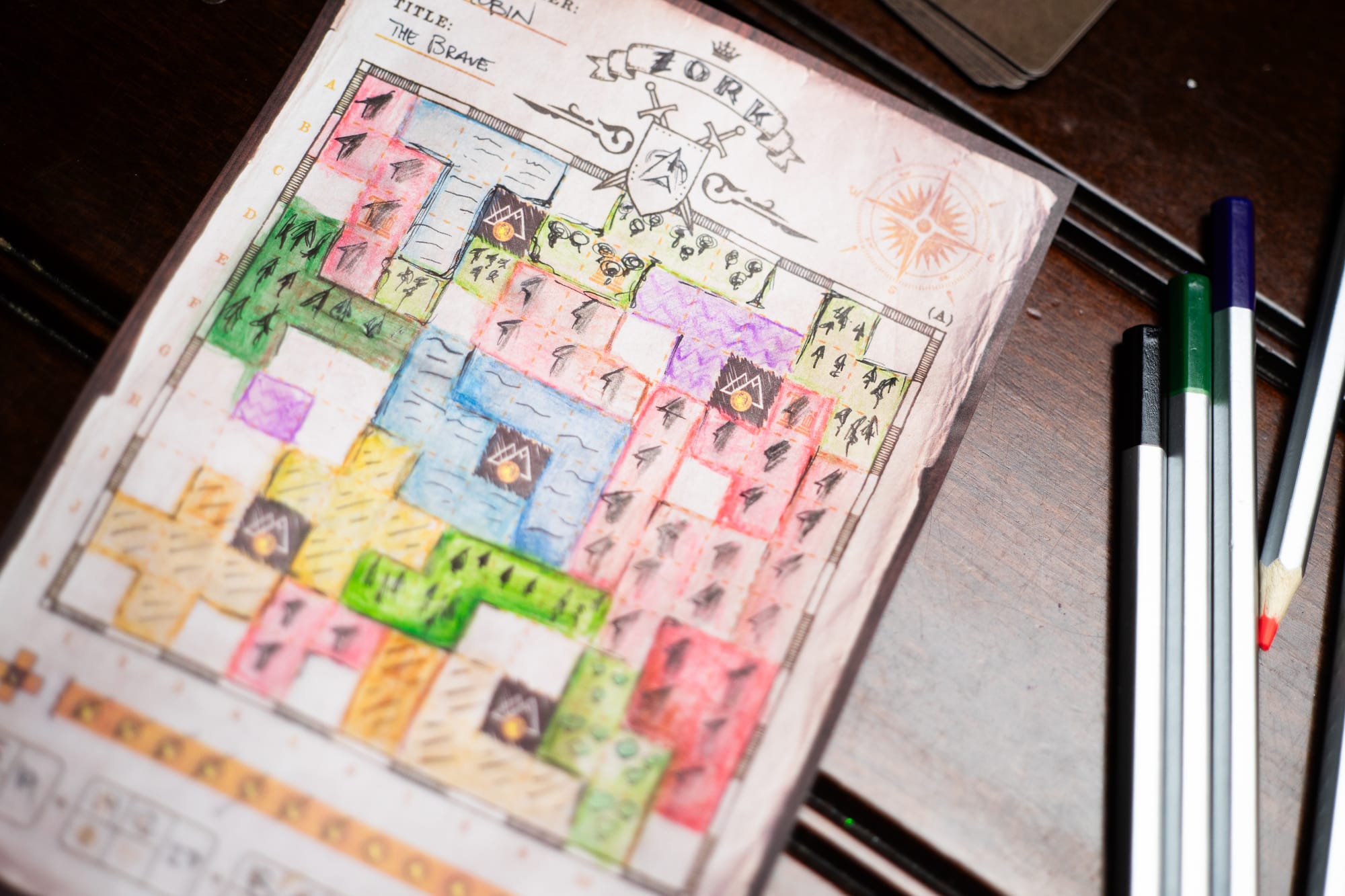

Cartographers

There is something so pleasant about a game where you fill in a map. Carcassonne (Wrede, 2000) is probably my favorite example. Twinkle Twinkle (Anderson, 2025) is a fun recent game with that sort of idea. I like to build out a map, and Cartographers (Adan, 2019) is a game that’s all about building a map. In each round, players will look to score points based on round-specific scoring conditions, with each condition used twice in the game. You’ll draw on your map based on a card drawn each round that features a specific shape and feature type — you’ll be drawing forests, homes, rivers, and fields.

Making the features fit together and capitalizing point-scoring opportunities will be satisfying and delightful, except for the rare cases where you draw the game’s sole interactive feature. Each round, you’ll add an enemy card to the game, and when that’s drawn, you have to pass your map to your neighbor, who will draw an enemy polyomino on your precious little map — and they don’t even have to make it beautiful. (They’re welcome to try, though.) Whether it’s beautiful or not, you have to surround enemy tiles with features or they’ll score negative points each round.

As you progress through the game, you’re looking at future scoring conditions, aiming to earn points with those as well as the ones immediately in front of you. If you can strike just the right balance, you could end up scoring big points in the late game, and that’s a great way to power yourself to success.

This isn’t the most complicated game in the genre, nor does it have the deepest strategy. What it does hold for players is a satisfying experience that can range from 30 minutes to several hours, dependent only on how detailed players want to make their drawings on their maps. That’s flexibility right there.

Designed by Jordy Adan, illustrated by Luis Francisco and Lucas Ribeiro, and published by Thunderworks Games.

Cascadia: Rolling Rivers and Rolling Hills

You’ve probably heard of Cascadia (Flynn, 2021), either because it won the prestigious Spiel des Jahres prize, or because it’s simply a really great game that’s had a bit of mainstream crossover success. In Cascadia, you’re basically expanding your map, playing animals on that map, and meeting a set of randomized scoring conditions that change each time you set up the game. (Wait, is this the same pitch I gave for Cartographers? Hmm!) It’s a puzzle you get to solve each time you play. That’s nice, right?

Cascadia: Rolling Rivers and Cascadia: Rolling Hills (Flynn, 2025) are a spinoff of Cascadia as a roll-and-write game. The two games are nearly identical, but we’ll get into the important differences as we progress. A lesser game would take the premise of Cascadia and adapt it into a roll-and-write game as best as possible, serving as an opportunity to capitalize on its success while remaining low-effort. Cascadia: Rolling is anything but low effort, and in a way, it’s anything but a solitary game. In each edition of the game, there are four game modes you can play, with the first three in each being shared — for all intents and purposes, they are identical.

Each of the modes progress in complexity, starting at a pretty breezy roll-and-write and ending with something involved and strategic. The fourth and final mode in each of Rivers and Hills is different, giving you a genuine reason to own both if you love the game. They’re not just cosmetic differences; they’re almost just completely different games.

That’s the great thing about this series. Each game mode could be its own game. When I said that a lesser game would just crib from Cascadia, we ought also consider that a lesser (and still very good game) would have packaged each different mode in its own box, served up a few offerings, and done reasonably well. It would’ve worked, but it wouldn’t be great.

Designed by Randy Flynn, illustrated by Beth Sobel, and published by Flatout Games and AEG.

Railroad Ink

If I had to describe what I loved about Railroad Ink (Hach and Silva, 2018) briefly, I’d focus on one major thing: It’s about the most straightforward implementation of network-building that I’ve come across. You can play the game in about 15 minutes, and it doesn’t suffer for it. Your turns feel meaningful as you pick from railroads and highways to draw on your 49-square board. Over six rounds, you’ll connect exits off the board with each other, earning points for connecting more exits. If you manage to connect each exit, you’ll score a whole bunch of points for the effort. Realistically, something will go wrong with a roll of the dice and you’ll have to compromise your vision.

All of that is excellent, and it’s my preferred way to play the game. I’ve rolled those four white dice hundreds of times, and though it lacks variety in experience, it doesn’t lack replayability. The puzzle is breezy enough that complicating it isn’t necessary — but if that’s what you’re interested in, there’s actually no shortage of options for you. See, the first iteration of the game came in two editions, one blue, one red. (There are later yellow and green editions. Yes, it’s very Pokemon.) Each edition comes with two sets of optional expansion dice that add some variety to the base game. You might add lava, meteors rivers or lakes in the red and blue editions, respectively. Add in a slew of expansion dice, each set of which alters the game in unusual ways, and you have a great roll-and-write game.

Designed by Hjalmar Hach and Lorenzo Silva, illustrated by Marta Tranquilli, and published by Horrible Guild.

Super-Skill Pinball

There is a certain generation of people for whom pinball holds an inescapable hold. Pinball arcades popped up around the country. The clanging of the ball as you fire it forward on the table, the unmistakable sound of the flippers as you desperately grasp at the ball before it plummets, because you’re not actually very good at pinball.

And then there’s a generation that grew up with Space Cadet Pinball on Windows 95. That’s my generation. I didn’t grow up going to pinball arcades (not because I didn’t want to, but because I grew up without one around), but I did spend hours upon hours playing pinball with Z, /, and the spacebar. This was a game that was absolutely captivating. Once I finally figured out how the missions worked, I wanted to play it even more.

Super-Skill Pinball (Engelstein, 2020) evokes that feeling, and it does it within the conceit of a roll-and-write game. It’s a game where the bonuses you can earn will get out of control, where you can end up with multiball, and where you’ll start racking up the points based on a few lucky rolls of the dice and some good planning. It’s a game that feels like pinball, even if it lacks the immediate action of a table. Between the original, Super-Skill Pinball: 4-Cade (2020), Ramp it Up! (2021), Star Trek: Super-Skill Pinball (2022), Holiday Special (2022) and DC Super-Skill Pinball: Harley Quinn Ball (2024), there are no fewer than 19 tables available to play. There are plenty of common features, but there’s also a lot to explore and master at each table, too.

Designed by Geoff Engelstein, illustrated by Gong Studios, and published by WizKids.

That’s Pretty Clever

If you were deep into board gaming in 2018, you might remember the clamor around Ganz schön clever (Warsch, 2018), a roll-and-write game that was purported to be pure fun. Plenty of people imported the game from Germany, where Schmidt Spiele first published it, and raved about it in forums and on podcasts. It was rapidly gaining steam, and it was hard to find. Perhaps that fueled the hype, though in my experience, it only does so temporarily — it rarely serves as a long-term boost, a lack of availability. When it finally came to the United States as That’s Pretty Clever, the hype had somewhat died down, but the respect it garnered among players remained. Wolfgang Warsch’s design had staying power, and it led to at least three more major iterations of the game, too.

The premise is simple: Each turn, a player will select a total of three dice from six possible, marking a space on their sheet for each. Whenever you select a die, you’ll move all dice with a lower value away; you can no longer select those dice. You’ll then roll the remaining dice, repeating the process until you have up to three dice in your area. All other players will then get to use the dice you haven’t picked. Because not every player is playing the same dice at the same time, instead getting to use one of the castoff dice, your turn feels meaningful. It’s not an infinitely scalable game like some on this list are. (This is not a slight, though.) The decisions other players make will have a meaningful impact on what you’re able to do.

And all of that is great, but the real joy of That’s Pretty Clever lies in how cleanly it executes the action selection bonus idea. You’ll be marking in a variety of types of spaces, and each type of space offers you different kinds of bonuses. Some will give you the ability to mark additional spots on your sheet, and you can potentially chain those actions several times. Careful planning in this game is rewarded, which is unusual for a reasonably light dice-chucking game. When those bonuses start firing off in sequence and you know you’ve done a good job, there’s great satisfaction unlocked.

Designed by Wolfgang Warsch, illustrated by Leon Schiffer, and published most recently in the U.S. by CMYK.

Thanks for reading this week’s edition of Don’t Eat the Meeples! I hope you’ve had a great week and have played some fun and exciting games. I didn’t get a ton of in-person plays in this week, but plays of Llama Llama (Miyano, 2025) and Tearable Quest (Ono, 2025) were both nice and breezy takes on light games. (This is only somewhat a lie. Tearable Quest is tense. It’s difficult. It requires great concentration. I thought it was very cool, but I am very bad at tearing paper in the ways I’ve planned.)