Five games to replace Mouse Trap

I wanted to love Mouse Trap as a kid. I wish I'd had these five games instead.

It’s time to build a better Mouse Trap. Or, you know, insert a better joke, if you’ve got one. It’s late.

Mouse Trap (Barlow, Glass, Kramer and Meyer, 1963) is a game I wanted to love as a kid. I saw the commercials. I saw the box. I understood that this was a game that equally a toy. It was my introduction to the Rube Goldberg machine. It was an unavoidable part of my childhood. My disappointment when I finally played the game? Unavoidable, too. I thought I was in for a great game with a great series of events that would result in the trap being sprung on my opponents.

These five games aren’t Rube Goldberg machines. I’ve yet to see a great game built with one. These are games with a bit of flair for raw, unadulterated fun. They’re games that rely on your dexterity, but they do it in a way that leads to exciting outcomes and big laughs. We’re not talking games that require a lot of skill, or at least we’re not talking about games that reward skill development. No Crokinole (1876), no KLASK (Bertelsen, 2014) — nothing of the sort. These aren’t games that you can get demonstrably better at, and they’re not games that would have great world championships planned around them. They are, however, games that you sort of think that maybe, with enough practice, you might be able to get good at. It’s that fine difference we’re looking for here.

Hamster Roll (Zeimet, 2000) is a game with a big ol’ wooden wheel and a slew of wooden pieces you’ll be placing on the inner rim of that wheel. As you place pieces on that inner rim, the wheel rolls, because wheels are designed to roll. It’s a great invention. The original mousetrap, if you will. This game’s funny, because as it rolls, most pieces shimmy around and eventually come to rest, but some will fall out, often spectacularly. When they fall out, you have to take pieces into your supply. If you get rid of all the pieces in your supply, you’ll win.

I don’t know why exactly Hamster Roll works as well as it does. It lacks the intricacy of a Rube Goldberg machine in all its glory, but as you place things on the wheel, a certain magic happens: You might think that you’re doomed to failure, but the piece you place fits, and it doesn’t ruin the game. That’s magic.

Designed by Jacques Zeimet, illustrated by Andrea Hofbeck and Stefan Sälzer, and published in the U.S. most recently by 25th Century Games.

Viking See-Saw (Knizia, 2021) is a game about placing pieces on a purple viking ship that rocks back and forth. Like a see-saw. You get the name. And that, on its own, really explains the bulk of the game. As in most dexterity placement games, when pieces fall off, you add them to your supply. In Viking See-Saw, you also have to take a wooden treasure chest piece whenever the ship rocks back to its other side. And all that would be fine — these pieces are relatively small, and if they were all made of wood, you wouldn’t have too much to deal with.

The pieces are not, you see, all made of wood. Two of your pieces are spheres; one is heavy, the other is light. When the ship moves, those round pieces move. You also have four metal cubes — and, again, two are heavy, the other two are light. Just when you think you’ve figured out how the weight of your pieces works in this game, something will happen that derails you. But, again, when something works unexpectedly, it’s exciting. Invigorating, even.

Designed by Reiner Knizia, illustrated by Yoshiaki Tomioka, and published by itten.

Rhino Hero (Frisco and Strumpf, 2011) is a game in a yellow box that will make you think it’s made only for children. This HABA-published game may be built for little hands (the listed age is 5+), but that doesn’t mean it’ll be particularly easy for adults to master. You’ll be building a tower with cards, and if that’s not the most satisfying thing for your inner child, I don’t know what is. For the number of times as a kid I wanted to build a house of cards and failed miserably, Rhino Hero is the cure.

Designed by Scott Frisco and Steven Strumpf, illustrated by Thies Schwarz, and published by HABA.

The Fuzzies (Hague, Vickers and Warsch, 2021) is perhaps best known by its premise: It’s Jenga, but instead of using wooden blocks, you’re using fuzzy balls. Your goal is to deconstruct a tower, piece by piece. The loser of the game is the player who knocks over the tower in the process — and it’ll happen, because we’re not all perfectly geared robots. This is a game that not only has a great toy factor, but it feels like a great toy. We’re so used to games being made of plastic, wood cardboard and paper. When a game is made with little bits of fuzz, it feels different.

Designed by Alex Hague, Justin Vickers and Wolfgang Warsch; illustrated by Adamantia Chatzivassileiou, and published by CMYK.

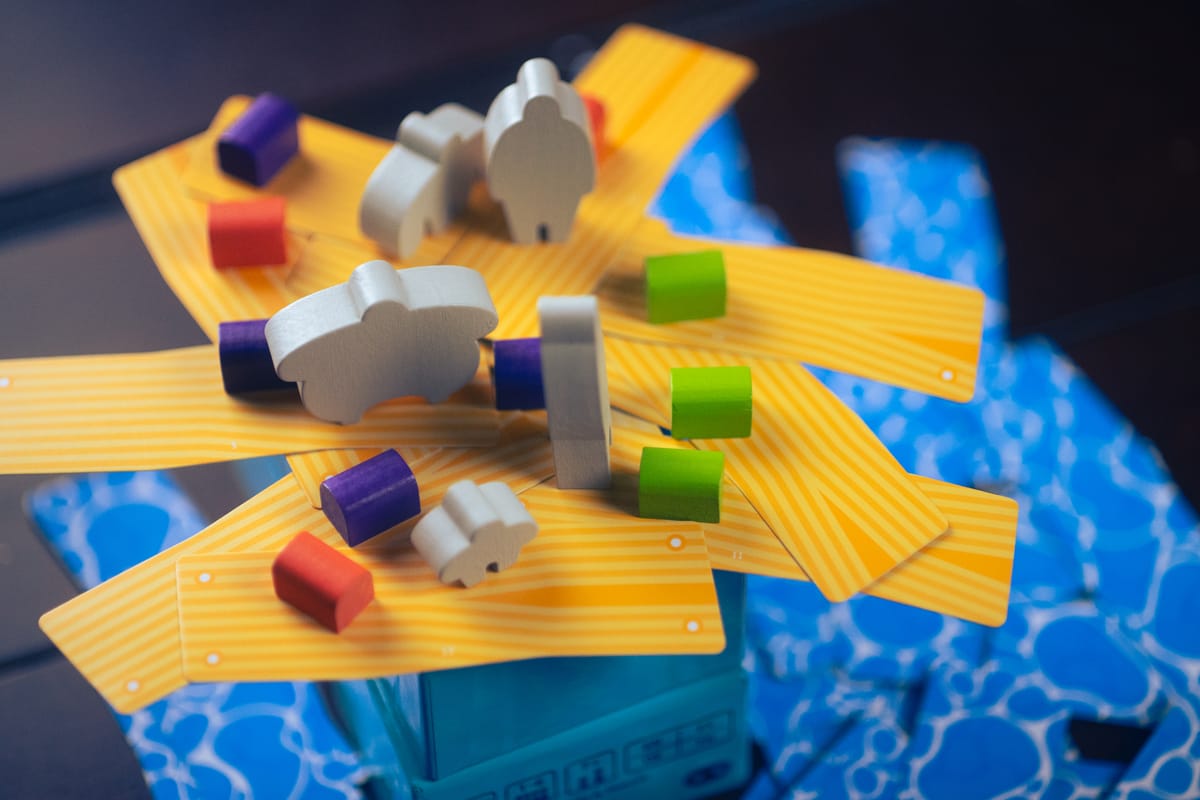

Rafter Five (Mashiu and Sasaki, 2023) rounds out our games today, and it’s a delightful little game of laying cards on the back of the game’s box to make a larger and larger raft. By playing with the box as the foundation of the game, you’re abandoning the expectations of a normal game. On each turn you play, you’ll be expanding the raft by playing more cards and sort of wedging them in place, often being held down only by a little wooden figure and some treasure chests. Rafter Five feels like it shouldn’t work — why should thin cards hold the weight of the figures and some treasure? The game works far better than I thought it would from the outset, and that’s delightful.

Designed by Mashiu and Jun Sasaki, illustrated by Jun Sasaki, and published by Oink Games.

Thanks for joining me at Don't Eat the Meeples this week, and my apologies for the late email. Life got in the way, as it sometimes does. I'll be back next week with something, though we'll see just what. Maybe I'll write about games that don't interrupt a good conversation.