14 'older' trick-taking games worth revisiting

Older, of course, is a relative term. These games were released over a decade ago.

If we can establish the early to mid 2010s as ‘the golden era of hobby board games’ — which I think we can do, and I think we can actually track it with the rise of cooperative board games — then I think it serves as a salient point of reference for trick-taking games. There’s an interesting caveat to consider, which is of course that trick-taking is not a novel concept in the 21st century, and it wasn’t a particularly novel one in the 20th century either. We traced back a little bit of the genre’s history last week, which I hope stood out in my long, rambling writing.

One thing I mentioned there is that I’d love to talk more about trick-taking games that aren’t new releases, to celebrate games that have come before the current era. Before I discuss any games, I’d be remiss to not reference the Trick-Taking Guild’s Golden Trickster Hall of Fame, which is meant to honor games that predate the Golden Trickster award’s creation, so games published before 2018. While we’re going to go at least eight years earlier than that, that list is incredible, and it includes some games we’ll talk about here.

I’ll also note that I’m not going to solely focus on trick-taking games, and I’ll include some climbing games as well. We could debate the merits of that if you’d like, and maybe we will someday, but I’m not going to get wrapped up in a discussion about microgenres today. (As somebody who ran a music blog in the mid-2000s, I think I might have had enough about that for one lifetime, but you know what? I’m sure I haven’t.)

Alright! Here we go.

Trick-takers published before 2010

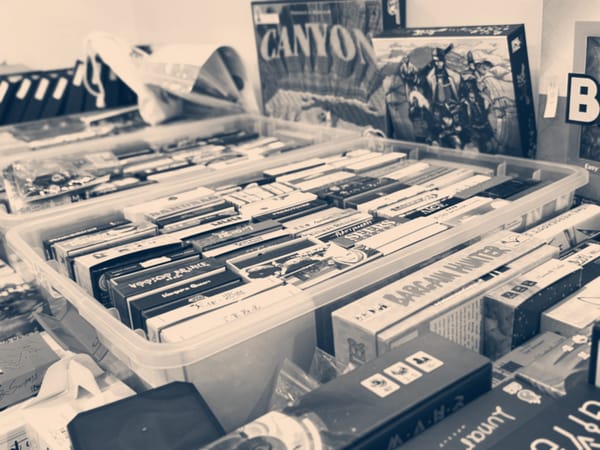

- Bargain Hunter (Rosenberg, 1998) is sort of half set collection, half trick-taking, and it’s by the guy who’s had an outsized influence on the hobby board gaming landscape. In this one, you’re trying to take tricks that match a specific item you’re trying to collect, but every other item than your goal (essentially) is worth negative points.

- The Bottle Imp (Cornett, 1995 and 2024) takes the classic Robert Louis Stevenson story and crafts a great trick-taking game around it. Basically, you’re trying not to be the last player stuck with the bottle, and you get the bottle by playing a card lower than the bottle’s active price. It’s not a perfect game, but it’s an important one, even if it the game has a knack for making you feel stuck in the mud sometimes. I think it’s an important part of a trick-taking education.

- Mü (Matthäus and Nestel, 1995) — I didn’t think I’d love Mü the first time I played it. That’s probably because it was on Board Game Arena, and the game went on for roughly six months. (I may be exaggerating this slightly, but I don’t think I am. It was a long, long time.) It’s not a beautifully illustrated game, though it certainly has its charm if you’re into German board games from the 1990s. I’m still not even sure I understand the scoring entirely, but I really have enjoyed my plays of this. The bidding system is a little wild, and I love variable partnerships, it turns out. (I’m not always the best partner, though. Sorry, teammates.)

- Wizard (Fisher, 1984) is one of the early modern trick-takers, and it’s pretty straightforward, except you’re playing a ton of rounds, and in each round, you have a hand size equal to the round number. With three players, you’ll play 20 rounds. 20! I do think this game gets long in the tooth, but that doesn’t make it a less interesting part of the trick-taking landscape. The game still does a nice job with a rotating trump and variable round scoring.

- Tichu (Hostettler, 1991) is at the top of the heap for so many fans of climbing games. It’s a fixed-partnership game, it features four special cards that influence play considerably, and players have opportunities to declare bids in the middle of a deal and at any point before playing card. A tremendous game, to be sure.

Trick-takers from 2010–2015

- Charms (Shinzawa, 2014) is one of the three 2014 Taiki Shinzawa trick-takers on this list. It’s a cool little double-card situation, where you’re either playing a suit card or a rank card, and you constantly have one of each in front of you. Charms (formerly Dois)

- luz (Shinzawa, 2014) is the famed Shinzawa trick-taker with hands that are splayed out for your opponents to see. In essence, it turns figuring out the strength of your hand into an exercise in inductive and deductive reasoning. Not every card will be in a player’s hand, of course,

- Maskmen (Shinzawa, 2014) is a great little climbing game. Its cards have no ranks, and the game is basically about luchadors battling it out in the ring for superiority. (You do have to imagine the bouts; this game could easily be themeless.) As you play a round, you’ll be establishing the relative priority of each suit, and how you establish that really should be done in a way that makes your hand work.

- Monster Trick (zur Linde, 2015) is an odd little game. The German release of this game makes it look like a game from 2005, not 2015. It’s a trick-taker where you aren’t just playing to one trick played sequentially after another; you’re playing to one of several tricks at the table. Your bid is played with three cards that you arrange in front of you and reveal at the end of the round, and each round has higher stakes than the one previous. It adds in a whole dynamic around off-suiting, bidding, and I really enjoy this game a lot.

- My Favourite Things (Nilgiri, 2015) is a weird game. It’s a trick-taking game where each player gets a set of cards in one color, and they’ll be writing, in rank order, their favorite things in a specific category. The ranks are then hidden, the cards are shuffled, and folks are then tasked with playing a trick-taking game where there are ranks, but they don’t know them, and they’ll have to compare players’ favorites in totally incommensurate categories. What a cool idea, and what a wacky game.

- Potato Man (Burkhadt and Lehmann, 2013) is the game that originated the must-not-follow concept, and while it’s not my favorite in the microgenre (ha! I fooled … me. I am talking about it, if just a tiny bit), it’s the first, and it does hold up well. A big twist here is that some low cards can beat some high cards — I dunno, it works well enough.

- Seas of Strife (Major, 2015) is my go-to trick-taker for groups of five or six. It’s quick to explain, but there’s a great twist: You want to avoid taking tricks, and you might end up with several suits in a single trick. The nautical theme is nice, and I like it more than its earlier Texas Showdown iteration, and its first iteration was entirely themeless. The development of this game is a fascinating story all its own, but that’s perhaps for another day.

- Trick of the Rails (Hayashi, 2011) is a trick-taking train game. Sure, it’s not a super in-depth 18XX game, but it’s still an interesting play on two genres. You’ll collect stock, place rails, all that. I don’t think anything’s since has really set out to do what Trick of the Rails does. That’s particularly interesting for two reasons: First, I think the game works well. Second, we see a lot of mechanism riffing in trick-taking (and, indeed, all board games — and it’s not a bad thing!) — so why not this one?

- Haggis (Ross, 2010) — Haggis is an iconic climbing-shedding game, and it holds an enduring spot in the ranks of trick-taking and climbing games. It has few tricks up its sleeve, but it does only what it needs. This is a game that treats its players seriously.

Trick-takers I really need to play

- Sluff Off! (Dorra, 2003) — Stefan Dorra designed what is likely my favorite new trick-taker I played this year, Skull Queen (2024). But he’s been designing trick-takers for nearly 30 years now, with Nyet! (1997) another of his that’s been on my to-play list for ages.

- Was sticht? (Schmiel, 2003) has two trumps, task-drafting, and variable goals. What’s not to love? I don’t know, actually, because I haven’t played it yet, but I’d like to.

- Cosmic Eidex (Hostettler, 1998) — This is a three-player-only trick-taker where each player has a special power that’s randomly determined before the game starts. And it’s based on Jass, which I’ve never played. (I’d like to play that some day, too, but we’re not focused on traditional trick-takers here.)

- Jalape-NO! (Kiesling and Kramer, 1998) — Some of these early modern trick-takers have huge decks. I wonder why that is. This one, originally published as Pepper, has a deck 108 cards large. Anyway, that’s kind of a tangent.

- Frank’s Zoo (Matthaüs and Nestel, 1999) — I’ve read the BoardGameGeek description for this game. I don’t understand it. “Players get points by playing all their cards, collecting lions, and collecting a hedgehog.” And this gem: “This is a climbing game, similar to The Great Dalmuti, Tichu, and others. The difference here is that the ranks are different kinds of colorfully illustrated animals.” I’m absolutely certain there’s more difference. I’d love to play this well-regarded classic.

Thanks, as ever, for joining me at Don't Eat the Meeples! Apologies for the day-lateness of this one — work threw some curveballs my way, but we got there in the end.